Inside AI Brains: How Anthropic Decoded Claude's Thinking Process

By Lucas Fernandes Aguiar

Anthropic recently published a fascinating paper with an unusual title: “On the Biology of a Large Language Model.” But what does biology have to do with AI? As it turns out, quite a lot. The researchers are essentially performing a digital dissection of Claude’s “brain” to understand how it thinks—and finding surprising parallels to biological systems along the way.

In this post, I’ll break down this complex research into digestible parts, explaining how scientists are starting to understand what’s happening inside these AI systems when they answer our questions or write poetry.

Why It’s Like Studying a Strange New Organism

When AI researchers create a large language model like Claude, they don’t program it step by step to solve problems. Instead, they train it on vast amounts of text and let it develop its own internal processes—much like how nature doesn’t design organisms with blueprints but shapes them through evolution.

This creates a fascinating challenge: how do you understand a system that nobody designed? The Anthropic researchers draw an explicit parallel to biology here. Just as biologists face challenges understanding complex evolved systems like the brain, AI researchers face similar obstacles with large language models.

This is why they call their approach “the biology of a large language model”—they’re essentially treating Claude as a strange new organism worthy of scientific study.

Digital Dissection: How They’re Studying Claude’s “Brain”

So how exactly do you dissect an AI brain? The researchers developed several ingenious techniques:

1. Attribution Graphs: Mapping Thought Pathways

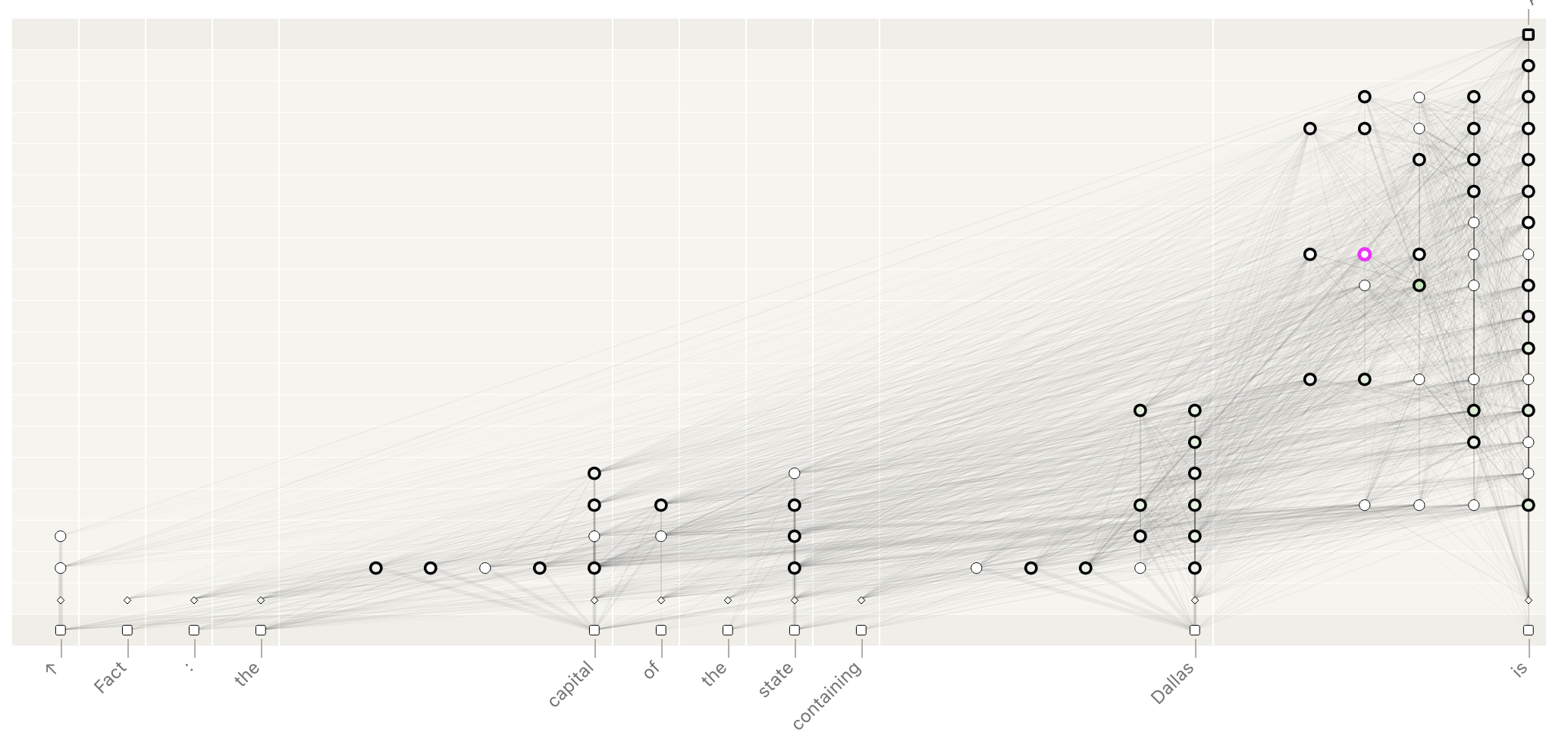

Imagine being able to watch thoughts flow through a brain in real-time. That’s essentially what attribution graphs do for Claude. These maps show how information moves through the model when it’s answering a question:

- Each node represents a concept or pattern the model has learned (called a “feature”)

- Lines between nodes show how these concepts influence each other

- The stronger the connection, the thicker the line

These graphs reveal the chain of “thoughts” leading from your question to the model’s answer.

2. Creating a Clearer View: The Replacement Model

One big challenge in understanding neural networks is that individual “neurons” often do multiple things—they’re “polysemous,” to use the technical term. It’s like trying to understand a city’s traffic by watching individual intersections that serve many different routes.

To solve this, the researchers created a “replacement model” with components that each do just one thing. Think of it as replacing a messy wiring diagram with a clearer one where each wire has just one purpose. This makes it much easier to understand what’s happening inside.

3. Testing Theories with “Digital Brain Surgery”

To confirm their understanding, researchers performed something akin to digital brain surgery. After identifying potential “thought pathways” in Claude, they temporarily modified specific parts of the model (similar to how neuroscientists might temporarily deactivate brain regions) to see if the effects matched their predictions.

When the model behaved exactly as they expected after these interventions, it confirmed they were on the right track in mapping its internal processes.

Validating the Findings: Intervention Experiments

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the methodology is how the researchers validated their hypotheses. Through intervention experiments, they perturbed specific features in the original model and observed the effects on other features and the model’s output.

These interventions are crucial for establishing causality rather than mere correlation. By inhibiting or enhancing specific features and observing the downstream effects, researchers can confirm whether the mechanisms identified in attribution graphs truly represent causal pathways in the model’s reasoning process.

When the effects of these interventions matched the predictions from their attribution graphs, it strengthened confidence that they had correctly identified the causal mechanisms at work. This approach is similar to how neuroscientists might use targeted stimulation or inhibition to understand brain circuits.

Operand Plots: Visualizing Numerical Processing

For specific tasks like addition problems, the researchers developed operand plots to visualize how features responded to different inputs. These plots revealed geometric patterns that showed how features were sensitive to different aspects of arithmetic operations—like focusing on individual digits or the final sum.

Case Studies: Circuit Tracing in Action

To better understand how this methodology works in practice, let’s look at some fascinating examples from the original paper:

Multi-Step Reasoning: Finding Dallas’s State Capital

One case study examined how Claude determines that Austin is the capital of the state containing Dallas. The attribution graphs revealed a multi-step reasoning process where the model:

- Identified Dallas as a city

- Determined that Dallas is in Texas

- Retrieved that Austin is the capital of Texas

- Generated the answer “Austin”

This closely mirrors how a human might solve the same problem, suggesting the model has developed logical reasoning circuits rather than just memorizing facts.

Poetry Planning: Anticipating Rhymes

Another intriguing discovery came from studying how Claude writes poetry. The attribution graphs showed that when writing a line that needs to rhyme with a previous line, the model activates features related to the rhyming word before it even begins writing the new line. This suggests the model engages in sophisticated planning, first choosing words that will rhyme and then constructing a line around them.

Lookup Tables and Domain Transfer

The researchers found that for arithmetic problems, Claude develops what resembles “lookup table features” that map digit pairs to their sums. Surprisingly, they discovered similar mechanisms being used for completely different domains, like retrieving academic citations, suggesting the model develops general-purpose computational strategies that it applies across diverse tasks.

The Discovery of Dual Circuits

One of the most significant findings was that Claude uses two distinct types of circuits:

- Language-specific circuits that process and manipulate linguistic information

- Abstract, language-independent circuits that handle general reasoning, planning, and computation

This dual architecture suggests that the model has developed specialized cognitive modules similar to those observed in human brains, where different neural circuits handle different aspects of cognition.

Limitations of the Methodology

Despite its power, the circuit tracing approach has important limitations:

- It struggles with very long reasoning chains that span many tokens

- It may not perform well on unusual or out-of-distribution prompts

- It’s better at explaining what the model does than why it doesn’t do something

- The replacement model, while interpretable, cannot perfectly capture all aspects of the original model (hence the need for error nodes)

The researchers’ openness about these limitations is itself valuable, reminding us that interpretability is still an evolving field.

Interactive Tools and Resources

For those interested in exploring further, the Anthropic team has released an interactive attribution graph explorer that allows you to navigate the circuits they discovered. This tool provides a hands-on way to understand how different features connect and interact within the model.

Try It Yourself: Interactive Exploration

For those curious to see these “neural pathways” firsthand, Anthropic has released an interactive attribution graph explorer. This tool lets you navigate through Claude’s thought processes yourself, seeing how different concepts connect and interact within the model.

Why This Matters for the Future of AI

This research isn’t just academic curiosity—it has profound implications:

Safety and Alignment

If we understand how AI systems actually “think,” we can better ensure they behave safely and as intended. Rather than treating them as black boxes, we can identify and modify specific circuits responsible for problematic behaviors.

Better AI Design

By understanding which internal structures are most effective for different tasks, future AI systems could be designed more efficiently, with purpose-built components for specific functions.

A Window into Cognition

Perhaps most intriguingly, these systems might teach us something about cognition in general. The fact that similar computational structures emerge in both artificial systems and biological ones suggests there may be universal principles underlying intelligence—regardless of whether it’s made of neurons or code.

Conclusion: Where Biology Meets Technology

Anthropic’s research represents a significant milestone in our journey to understand AI. By treating large language models not as mere software but as complex biological-like systems worthy of scientific study, they’ve opened new avenues for AI interpretability.

The discovery that these systems develop structured reasoning circuits, plan ahead when writing, and organize into specialized subsystems suggests they may be developing computational strategies that parallel aspects of human cognition. This doesn’t mean they’re “thinking” like humans, but rather that certain computational architectures may be particularly effective for language and reasoning tasks—whether they emerge in biological brains or artificial neural networks.

As this field of “AI biology” continues to develop, we may find ourselves with not just more powerful AI systems, but ones whose inner workings we can truly understand and explain. And in doing so, we might just learn something profound about the nature of intelligence itself.

What do you think about these discoveries? Does the fact that AI systems seem to develop specialized “brain regions” surprise you? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

You can reach out to contact me about this and other topics at my email [email protected] or by filling the form below.